A conversation with Erik Underwood of Basis Climate and James Coombes of Conductor Solar

When the Inflation Reduction Act passed in 2022, Erik Underwood and his co-founder read the legislation, saw the part about tax credit transferability, looked at each other, and knew they needed to start a company.

“The joke is we read the IRA and ran off to Delaware to incorporate,” Underwood laughs. What they saw wasn’t just a new tax policy. They saw the dismantling of one of the most frustratingly exclusive markets in clean energy finance and an opportunity to rebuild selling solar tax credits from the ground up.

That market was traditional tax equity, and Erik says “oligarchic” is probably the kindest word for it. A handful of large investors controlled access to solar tax incentives, cherry-picking the biggest deals and dictating terms to everyone else. Small and mid-sized projects were effectively locked out. The IRA changed the rules of the game entirely—but as Erik and James Coombes of Conductor Solar made clear in a recent conversation on the Renewable Rides podcast, understanding how to play by those new rules takes some work.

What is a Tax Credit Transfer?

At its core, a tax credit transfer is elegantly simple. When you install a commercial solar system, you generate federal Investment Tax Credits (ITC) equal to roughly 30% of eligible project costs. Before the IRA, using those credits required either having significant tax liability yourself or entering into a complex financial partnership with an institutional investor who did. Now you can simply sell them to any corporate taxpayer without a partnership or an investor taking a stake in your project.

For example, on a $1 million solar installation, that’s $300,000 in credits you can sell. Tax credit buyers typically pay 80 to 90 cents on the dollar, so you might net somewhere around $250,000 to $270,000 after transaction costs. The buyer gets a discount on their tax bill and the seller gets cash upfront. On paper, it sounds almost too straightforward. The reason it isn’t quite that simple is that the mechanics of actually executing a transfer involve timing, documentation, buyer dynamics, and structural considerations that can trip up even experienced project owners. Getting it right means understanding not just what the process is, but why it works the way it does.

Why Sell at a Discount?

The first thing that stops many business owners in their tracks is the idea of selling something worth $300,000 for $250,000. If you have tax liability, why wouldn’t you just use the credits yourself and keep the full value?

It’s a fair question, and Underwood’s answer reframes how most people think about solar project economics. The issue isn’t whether you can use the credits, it’s when. Solar projects are front-loaded by nature: high capital costs upfront, with energy savings and revenue accumulating gradually over time. Layered on top of that, depreciation deductions and operating losses create what Underwood describes as a “depreciation NOL balance,” essentially a pile of deferred tax assets that absorb your taxable income for years before your solar tax credits even get their turn.

“It’s often going to be seven, eight, or more years before you actually start benefiting from that credit,” he explains. “Your operating profit from the project normally will not outweigh being able to sell it at a slight discount on a net present value basis.”

In other words, the discount you take today is almost always worth less than the value of having that cash in year one instead of year eight. VECKTA’s Dan Roberts, puts it this way: “If we treat the tax credits just like another form of cash flow in the project, the more we can recuperate all of that cash flow in year zero or year one, the better our net present value.” Underwood agreed—and added that there’s another urgency to acting in that first year. Buyers can only purchase credits from the same tax year they were generated. The window doesn’t stay open forever.

A Framework for Thinking Through Your Options

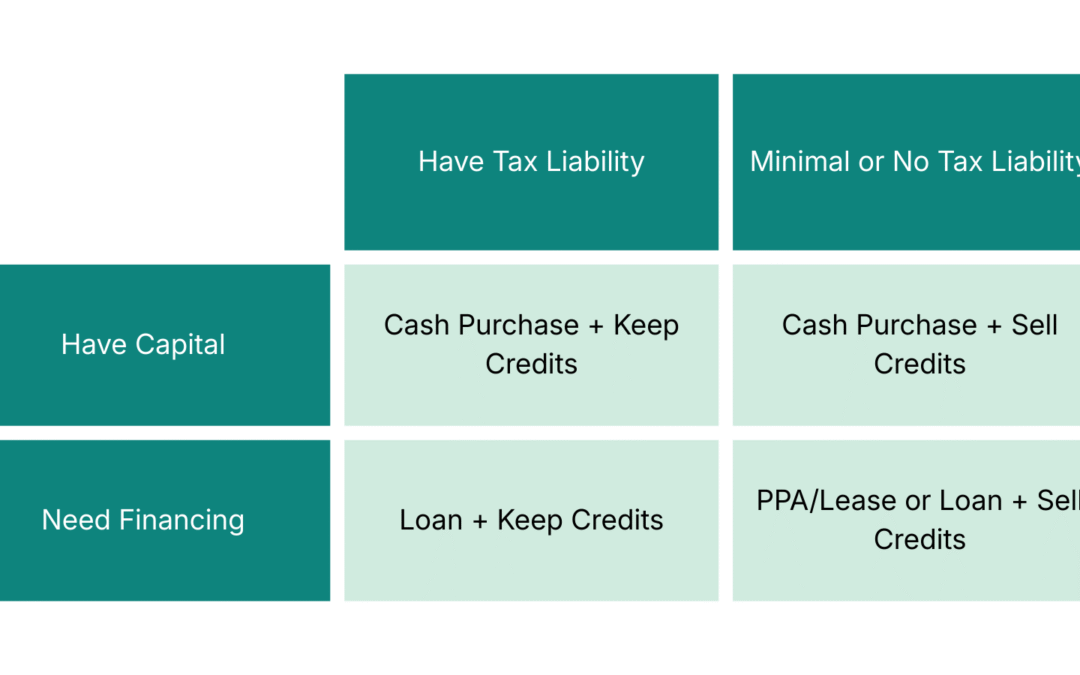

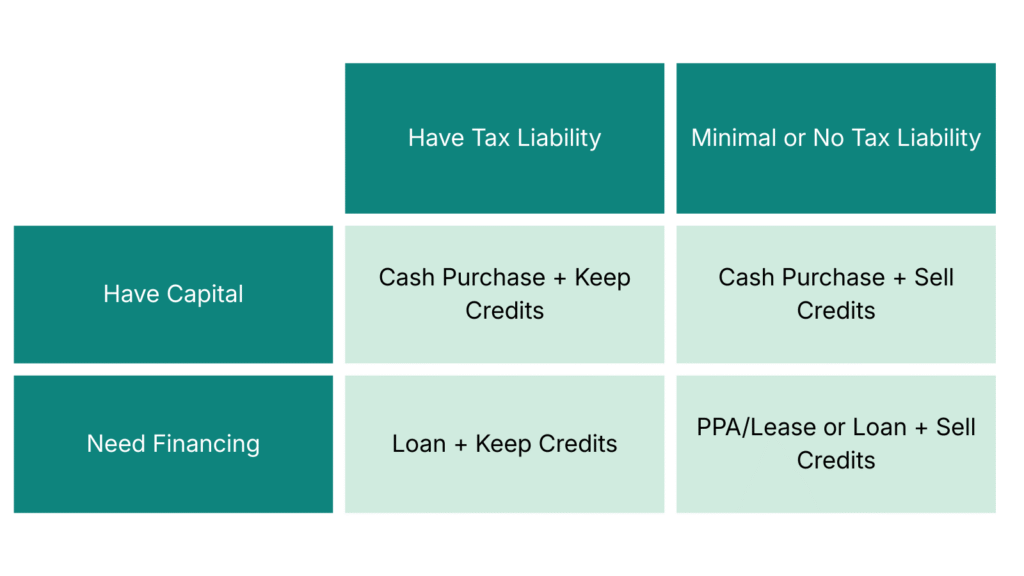

Not every business is in the same position when it comes to solar financing, which is why Coombes developed what he calls “the Matrix”—a simple two-by-two framework that cuts through the complexity and helps project owners figure out which path actually makes sense for them. The framework asks two questions: Do you have the capital to fund the project, or do you need to borrow? And do you have meaningful tax liability, or not? Depending on where you fall, the right answer could be a straightforward cash purchase, a loan, a power purchase agreement, or a tax credit transfer—and often some combination.

The interesting cases are the ones in the middle. A business with capital but limited tax liability is, as Coombes puts it, “a strong candidate” for transfer—pay for the project yourself and sell the credits to someone who can use them. A business with tax liability but limited access to capital might use a loan to fund construction and then monetize the credits to improve their payback. Investment-grade companies might have plenty of capital but still prefer to offload the tax credit and free up cash for other uses.

What Coombes emphasizes is that these decisions don’t always have to be made upfront. His firm has these conversations with clients at every stage—development, construction, and even after a project is already operational. “Clients will often decide they can potentially take the tax credit, but it’s going to involve some uncertainty on their income,” he explains. For agricultural businesses especially, the cyclicality of revenue makes it genuinely hard to predict future tax liability years out. Selling the credit removes that uncertainty entirely.

What Buyers Need—And Why the Underwriting Exists

If there’s one thing that catches sellers off guard, it’s the amount of documentation and diligence that buyers require. The natural reaction when you’re selling a $300,000 asset is to wonder why this feels more complicated than a real estate transaction.

The answer has two parts. The first is fraud prevention. The IRS built meaningful safeguards into the transfer system, including a registration requirement on its Clean Energy Credits platform, which is a process that ties each credit to a specific facility and taxpayer. This process currently takes up to four months to complete. Buyers must attach transfer election statements and registration numbers directly to their tax filings. The system is designed to make sure credits can only be sold once and that they’re legitimate.

The second part is buyer risk. Most corporate buyers purchasing tax credits are not solar companies. They’re manufacturers, retailers, financial firms, or mid-market businesses whose CFO heard about this and asked the tax director to look into it. They’re taking a five-year exposure on a project they didn’t build and won’t operate. Even if everything is done correctly, the IRS could audit the credits. The buyer wants to know that if something goes wrong, they have protection and that’s where indemnification provisions come in.

Underwood is empathetic about the seller’s perspective here. “The buyers want a risk-free credit effectively,” he says. “They’re taking a bet on something they’re not familiar with, on a project they’re not operating day to day.” The underwriting—financial statements, project documentation, cost breakouts from the contractor, utility letters—is what bridges that distance and makes buyers comfortable enough to write the check.

Coombes adds important context on recapture risk, specifically, which is often the provision that gives sellers the most pause. “The recapture provisions are not unique to a transfer of the credit,” he points out. “They apply on every system.” If you install solar and plan to keep the building and the system running for five years, you were already implicitly accepting recapture risk. Transferring credits doesn’t add new obligations so much as it makes the existing ones explicit and documented.

The Pricing Reality for Smaller Credits

The tax credit transfer market has a scale problem that both Underwood and Coombes are actively working to solve. The mechanics and economics of large deals ($10 million or more in credits) are well established. Big Four accounting firms understand the asset class. Fortune 500 companies have approved the product internally. Insurance carriers have developed policies. The market at that scale is genuinely liquid.

Smaller credits tell a different story. For a single-site manufacturing company or an agricultural operation that generates a $300,000 or $500,000 in credits, traditional tax credit insurance is often uneconomic. The upfront and policy costs can eat too much of the transaction value to make sense. The buyer universe looks different too: corporate buyers with formal approval processes and conservative tax directors may find the credit size too small to justify their internal overhead.

What’s emerging to fill that gap is a combination of alternative credit structures and a growing high-net-worth buyer market. Personal guarantees, parent company guarantees, and letters of credit substitute for insurance at smaller deal sizes. For companies Coombes describes as the “50/50 Club”—businesses with 50 years of operating history and a $50 million balance sheet—strong fundamental underwriting can be enough on its own. “A buyer can look at that and say, I can underwrite this on its own without credit support in the form of guarantees,” he says. “Those businesses should be able to transact without those kinds of credit enhancements.”

Basis has developed a specific product called Bolt to address the $250,000 to $2.5 million range directly by offering a streamlined, standardized process that bundles insurance into the transaction package and keeps costs predictable. Underwood is candid about why the floor sits at $250,000 for now: their insurance partners wanted to see the product work reliably before scaling further down. But the direction of travel is clear. “The idea is how do you standardize and keep it going so that you can do smaller and smaller deals?” he says.

Timing Is Everything—And Most Sellers Get It Wrong

If the documentation requirements are the most surprising part of the process, timing is probably the most consequential. And the single most important piece of advice from Underwood is so important he repeats it five times in quick succession during the conversation: do not file your taxes early.

The reason is simple but easy to overlook. You can sell tax credits at any point up until you file your tax return for the year in which they were generated. If you file on time in April, you’ve just given away six months of potential flexibility. If you extend—which you can do without penalty as long as you’ve paid your estimated taxes—your window stretches all the way to September or October.

That flexibility matters enormously, particularly for smaller credits, because of the way the buyer market moves through the year. Corporate buyers tend to be most active between April and August, but they often go dark in late August as they start closing out their own fiscal year-end processes. High-net-worth buyers, who are subject to different passive income rules that determine what income qualifies for clean energy credit purchases, tend to come in later—sometimes as late as May or June of the subsequent year, looking for credits from the prior tax year.

“There is a premium on high-net-worth buyers that have more flexibility, especially around later in the tax year execution,” notes Coombes. For a seller with a smaller credit who filed an extension, that September window with a motivated high-net-worth buyer could be the difference between getting a deal done and missing the market entirely. The corollary is equally important: don’t wait until late August to start the process, expecting to close before October 15th. Between IRS registration timelines, diligence requirements, and buyer approval processes, three to six months is a realistic expectation from engagement to cash.

A Special Note for REITs

Real estate investment trusts occupy a unique and somewhat frustrating position in the tax credit transfer market. Because of their pass-through structure, REITs don’t have a single direct taxpayer in the conventional sense, which creates complications for who can actually sell the credits and what kinds of commitments they can make to buyers.

The most common workaround is a Taxable REIT Subsidiary, a separate business entity that can hold the solar project and serve as the credit seller. For larger, financially strong REITs with long-term hold strategies, this structure can work well. And those REITs’ balance sheet strength often means they can put a direct guarantee behind the credits and skip expensive insurance entirely. But Coombes is honest about what he sees in practice. “The primary reason we see REITs not pursuing tax credit sales is the idea of taking on indemnities for five or more years,” he says. REITs built around active asset repositioning—buying, improving, and selling properties on a regular cycle—are naturally reluctant to take on a five-year commitment that could complicate a future sale. Partnership structures with multiple investors add another layer of complexity around who can actually provide guarantees.

For REITs that want to access solar tax incentives but can’t make direct transfer work, third-party ownership structures developed before the IRA remain an option. They’re less financially attractive than direct transfer, but they’re flexible enough to work for portfolios with planned disposition timelines. As Coombes puts it, the ideal REIT candidate is credit-worthy, has a long-term hold view, and operates in a clean partnership structure where decision-making authority is clear. Those deals can and do get done.

Where the Market Is Headed

Both Underwood and Coombes see the tax credit transfer market at a genuine inflection point, one that feels a lot like where solar PPA financing was about fifteen years ago. Back then, utility-scale deal structures were being awkwardly applied to small commercial projects, and the market was too rigid to serve nonprofits, schools, and houses of worship that needed different structures and different investors. Eventually, the market evolved. Specialized investor pools emerged with specific appetites, transaction costs came down, and previously inaccessible projects got financed.

The same maturation is happening now with transfers. Standardized products are making smaller deals viable. High-net-worth buyer networks are developing. Industry-specific investor pools with comfort in agriculture, manufacturing, or real estate are starting to form. “Somebody made a lot of money figuring out the market for non-investment-grade bonds,” Coombes observes. “That’s the opportunity here.”

None of this means the process is frictionless today. Buyers still need education. Smaller credits still require more work to place. Timing still catches sellers off guard. But for commercial property owners and project developers willing to engage with the process seriously by starting early, getting their documentation in order, and working with advisors who are honest about real market conditions, tax credit transfers are an increasingly powerful tool for improving project economics and accelerating the payback on clean energy investments.

This post is based on Episode #106 of Renewable Rides, the podcast from VECKTA about taking advantage of onsite energy. Listen to the full conversation with Erik Underwood of Basis Climate (buildwithbasis.com) and James Coombes of Conductor Solar (conductor.solar).